One of the most striking aspects of our North American Culture is the incentive it holds out for us to be invulnerable. This incentive is not consciously and clearly presented to us, yet is such a pervasive part of our culture that we succumb to its pressure without realizing it. Our resulting invulnerability seems to develop from an almost exclusive emphasis on the pursuit of mastery, efficiency, and control as the only valid signs of excellence. We are left with the result of well-managed, smooth-running lives that “work.” We achieve successful lives, and our security and acquisitions become material proof of this achievement.

In contrast, we have human suffering and vulnerability. Beneath our facade of efficiency and competence is our woundedness and our mystery. It is understandable that this vulnerability has never been very popular. Maybe the “vulnerable look” of a new Hollywood star can be engaging and may draw the crowd, but being or feeling vulnerable oneself is certainly not something to which one aspires. Indeed, it is the very essence of being vulnerable that it claims us in spite of our best intentions. If one were to aspire to vulnerability, its “achievement” would become just another version of good old mastery and success. Authentic vulnerability, unlike some other human states of being, is not “marketable.” To attempt to sell our vulnerability is to “close the wound,” and once again become invulnerable.

There is nothing new in the idea that there is value in our vulnerability. It is an ancient theme richly expressed in the roots of Western thought – found in both Old and New Testaments, and in the philosophy and tragic theater of the Greeks. It is the theme of vulnerability making for greater humanness, essential humanness.

Consequences of rejecting our vulnerability

The consequences of rejecting our limits and our suffering are all around us. When we reject these aspects of our existence, we must then defend against the continuing “danger” of encroaching weaknesses. In refusing to accept our limits, we implicitly judge human nature as not good enough, and in need of improvement. Our lives, then, fall victim to a perpetual perfectionism, a haunting and never-ending cycle of self-improvement. The deadly illusion of human progress as essential to human happiness is set in motion. If things do not progress or improve satisfactorily, the “enemy” or even the neighbor is blamed. In the Brave New World of efficiency and solutions to all problems, persons as they are cannot be tolerated. Persons are valued only for what they can produce, or for what they can master. They are valued for their output and their “good results.” In such a world there is no place for human error or confusion.

When we blot out or discard our intrinsic human value (our vulnerabilities) because they do not promote, accomplish, prove, or accumulate success, then we throw away a basic part of us that is real. As a consequence, we will have smoothed out all our rough edges and we can then fit anywhere, swallow anything, because we have become interchangeable with anybody in the crowd.

There is a kind of violence in this denial of vulnerability, a violence which levels the peaks and valleys of our experience, which erases the complexities, contradictions, and ambiguities of life. Our own human nature, with all its idiosyncrasies and imperfections, with all its surprises and dazzling turns, is mastered out of existence.

One could devote an entire essay to the relationship between the failure to tolerate human limits and weaknesses (the failure to be compassionate) and the actual physical violence so epidemic in our society. In a land of “instant availability,” no limits, and the inability to accept weaknesses in oneself or in others, we have the groundwork for literally ruling out human lives.

Something is missing

Many persons who know themselves, and are known by others, for their success, are haunted nonetheless by a certain feeling of emptiness in their achievements. We all wish and need to feel effective, and yet so often the satisfaction derived from our success leaves us with the feeling that something yet undiscovered and basically important is still missing.

What is missing, perhaps, is the value of vulnerability, the value in realizing that we are living a life which we cannot command. Such a realization can bring with it an exhilarating sense of freedom. The acceptance of our vulnerability can ease and soften the often harsh, ugly, manipulative, and pseudo-heroic values which would seek to rule our lives. Perhaps it is this glimmer of awareness: that what we really are beyond all the strivings for success, beyond all the happy disguises, is more profound, more lasting, and more worthy of respect than the latest victory over someone or some thing.

The Ugly Duckling becomes the Swan

We are faced with the following paradox: that what is often painful, difficult, even humiliating, when seen later in the light of increasing wisdom and healing time, sometimes turns out to be the most revealing of who we are and what it means to be human. There is a certain way we have, through our many successes and conquests, of disguising or entirely eliminating that fundamental human weakness, quirk, or sadness. Yet to our amazement, these vulnerabilities can later be experienced as our anchor in the storm, and as our true beauty and strength. It is something like the “ugly duckling” part of us which, upon an inner development and acceptance, becomes the swan.

When we think about our relationships, it is also interesting to note the power of attraction and deep satisfaction in being with another person who is vulnerable. It is not that we love failure or weakness for its own sake, but that there is perhaps nothing more fundamental than sharing in another person’s pain, need, or perceived failure. It is no less important or less human to share in another’s success, but nothing that I can think of links us together as human beings more than our shared struggles and difficulties. When we know and love someone in the deepest sense, do we not love, know, and accept them in their vulnerability? And are we not most caught up in the rough waters of self-knowledge when we are attempting to acknowledge or come to terms with our own vulnerability?

Once again we find that strange joy and freedom in being without disguise in the moment of a shared failure, or in the recognition and acceptance of defeat. In these moments we are in a realm of awareness beyond the self-imposed goals and expectations of the day. We are in the realm of what is real and what is true about which we can do nothing. Therefore we accept – and then, blissfully, we are without disguise.

Through the experience of our limits and the acceptance of our vulnerabilities, we are able at least temporarily to relinquish our false, defensive selves, and to experience the authenticity of being more simply human. The value of this is beyond measure.

As humans, we are never finally “arrived,” always open to new vulnerability. Our aspirations remain alive not only because of human heart and courage, but also through the redeeming force of our self-acceptance. Human knowledge becomes, then, a recognition of the depths of human beings, and the joy of accepting that these depths are beyond any technical knowing.

Raymond Keen

PSC 80 Box 21007

APO AP 96367-0095

rayboysan@gmail.com

Publishing history of “The Value of Our Vulnerability:”

Published as Sunday opinion article in The Richmond Independent (daily newspaper in Richmond, CA) on August 24, 1980.

The consequences of rejecting our limits and our suffering are all around us. When we reject these aspects of our existence, we must then defend against the continuing “danger” of encroaching weaknesses. In refusing to accept our limits, we implicitly judge human nature as not good enough, and in need of improvement. Our lives, then, fall victim to a perpetual perfectionism, a haunting and never-ending cycle of self-improvement. The deadly illusion of human progress as essential to human happiness is set in motion. If things do not progress or improve satisfactorily, the “enemy” or even the neighbor is blamed. In the Brave New World of efficiency and solutions to all problems, persons as they are cannot be tolerated. Persons are valued only for what they can produce, or for what they can master. They are valued for their output and their “good results.” In such a world there is no place for human error or confusion.

When we blot out or discard our intrinsic human value (our vulnerabilities) because they do not promote, accomplish, prove, or accumulate success, then we throw away a basic part of us that is real. As a consequence, we will have smoothed out all our rough edges and we can then fit anywhere, swallow anything, because we have become interchangeable with anybody in the crowd.

There is a kind of violence in this denial of vulnerability, a violence which levels the peaks and valleys of our experience, which erases the complexities, contradictions, and ambiguities of life. Our own human nature, with all its idiosyncrasies and imperfections, with all its surprises and dazzling turns, is mastered out of existence.

One could devote an entire essay to the relationship between the failure to tolerate human limits and weaknesses (the failure to be compassionate) and the actual physical violence so epidemic in our society. In a land of “instant availability,” no limits, and the inability to accept weaknesses in oneself or in others, we have the groundwork for literally ruling out human lives.

Something is missing

Many persons who know themselves, and are known by others, for their success, are haunted nonetheless by a certain feeling of emptiness in their achievements. We all wish and need to feel effective, and yet so often the satisfaction derived from our success leaves us with the feeling that something yet undiscovered and basically important is still missing.

What is missing, perhaps, is the value of vulnerability, the value in realizing that we are living a life which we cannot command. Such a realization can bring with it an exhilarating sense of freedom. The acceptance of our vulnerability can ease and soften the often harsh, ugly, manipulative, and pseudo-heroic values which would seek to rule our lives. Perhaps it is this glimmer of awareness: that what we really are beyond all the strivings for success, beyond all the happy disguises, is more profound, more lasting, and more worthy of respect than the latest victory over someone or some thing.

The Ugly Duckling becomes the Swan

We are faced with the following paradox: that what is often painful, difficult, even humiliating, when seen later in the light of increasing wisdom and healing time, sometimes turns out to be the most revealing of who we are and what it means to be human. There is a certain way we have, through our many successes and conquests, of disguising or entirely eliminating that fundamental human weakness, quirk, or sadness. Yet to our amazement, these vulnerabilities can later be experienced as our anchor in the storm, and as our true beauty and strength. It is something like the “ugly duckling” part of us which, upon an inner development and acceptance, becomes the swan.

When we think about our relationships, it is also interesting to note the power of attraction and deep satisfaction in being with another person who is vulnerable. It is not that we love failure or weakness for its own sake, but that there is perhaps nothing more fundamental than sharing in another person’s pain, need, or perceived failure. It is no less important or less human to share in another’s success, but nothing that I can think of links us together as human beings more than our shared struggles and difficulties. When we know and love someone in the deepest sense, do we not love, know, and accept them in their vulnerability? And are we not most caught up in the rough waters of self-knowledge when we are attempting to acknowledge or come to terms with our own vulnerability?

Once again we find that strange joy and freedom in being without disguise in the moment of a shared failure, or in the recognition and acceptance of defeat. In these moments we are in a realm of awareness beyond the self-imposed goals and expectations of the day. We are in the realm of what is real and what is true about which we can do nothing. Therefore we accept – and then, blissfully, we are without disguise.

Through the experience of our limits and the acceptance of our vulnerabilities, we are able at least temporarily to relinquish our false, defensive selves, and to experience the authenticity of being more simply human. The value of this is beyond measure.

As humans, we are never finally “arrived,” always open to new vulnerability. Our aspirations remain alive not only because of human heart and courage, but also through the redeeming force of our self-acceptance. Human knowledge becomes, then, a recognition of the depths of human beings, and the joy of accepting that these depths are beyond any technical knowing.

Raymond Keen

PSC 80 Box 21007

APO AP 96367-0095

rayboysan@gmail.com

Publishing history of “The Value of Our Vulnerability:”

Published as Sunday opinion article in The Richmond Independent (daily newspaper in Richmond, CA) on August 24, 1980.

Published in Communiqué, the monthly newspaper for “The National Association of School Psychologists” (NASP) in their March 2000 edition.

+++

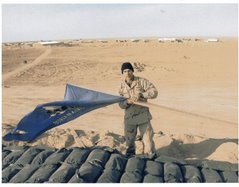

Brief Biography of Raymond Keen

RAYMOND KEEN was born in 1941 in Pueblo, Colorado. He graduated with a B.A. degree in Psychology from Case Western Reserve University in 1963 and an M.S. degree in Clinical Psychology from the University of Oklahoma in 1966. Upon graduation, he received a direct commission as a Navy officer, serving as a Clinical Psychologist for three years in the Medical Service Corps. One year of his Navy service was spent in Vietnam (1967-68) with the 1st Marine Division, 1st Medical Battalion near Da Nang. Since his active duty, he has worked primarily as a School Psychologist. He has spent 12 years overseas with the Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DODDS), working in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and Iwakuni, Japan. Raymond worked with the Marine Corps Community Services Counseling and Family Advocacy Program in Okinawa, Japan, as a Licensed Mental Health Counselor for 2 ½ years before retiring in April 2006. He lives with his wife, Kemme, who is a DODDS teacher on Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Japan.

Raymond has recently completed his first volume of poetry, Down In Heaven, Up In Hell. He is attempting to obtain publication for this volume at the present time. Five of his poems were published in the July/August 2005 issue of The American Poetry Review. He has also written a play, The Private and Public Life of King Able, unpublished. He is planning to write a non-fiction book, The Betrayal of Experience, which is critical of the “medical model” of Western psychiatry. Mr. Keen believes that poetry can uniquely affirm human experience in all its richness, darkness, confusion, and beauty.

RAYMOND KEEN was born in 1941 in Pueblo, Colorado. He graduated with a B.A. degree in Psychology from Case Western Reserve University in 1963 and an M.S. degree in Clinical Psychology from the University of Oklahoma in 1966. Upon graduation, he received a direct commission as a Navy officer, serving as a Clinical Psychologist for three years in the Medical Service Corps. One year of his Navy service was spent in Vietnam (1967-68) with the 1st Marine Division, 1st Medical Battalion near Da Nang. Since his active duty, he has worked primarily as a School Psychologist. He has spent 12 years overseas with the Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DODDS), working in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and Iwakuni, Japan. Raymond worked with the Marine Corps Community Services Counseling and Family Advocacy Program in Okinawa, Japan, as a Licensed Mental Health Counselor for 2 ½ years before retiring in April 2006. He lives with his wife, Kemme, who is a DODDS teacher on Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Japan.

Raymond has recently completed his first volume of poetry, Down In Heaven, Up In Hell. He is attempting to obtain publication for this volume at the present time. Five of his poems were published in the July/August 2005 issue of The American Poetry Review. He has also written a play, The Private and Public Life of King Able, unpublished. He is planning to write a non-fiction book, The Betrayal of Experience, which is critical of the “medical model” of Western psychiatry. Mr. Keen believes that poetry can uniquely affirm human experience in all its richness, darkness, confusion, and beauty.

2 comments:

Thanks, Ray. It strikes a cord with all of us, and I know I wouldn't trade all of mine for the world.

We hope to hear more from you!

De'on,

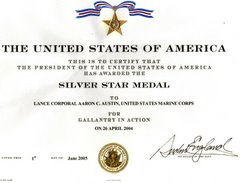

Your generosity of spirit and courage in sharing your love and loss of Aaron has had a wonderfully healing effect on our wounded warriors and their loving and grieving families. You have touched this Vietnam Vet's heart with your honesty, courage, and vulnerability, for sure.

Semper Fidelis

Okinawa, Japan

Post a Comment