Where we left off …

No bookmaker would have bothered to give odds on the outcome of the battle. The Americans launched 26,000 troops with massive air support in a night-time attack against about 3,500 soldiers of the Panama Defense Forces distributed in isolated garrisons throughout the republic. It is remarkable that Noriega’s army offered any resistance at all, knowing full well the might of the military machine which had been launched against them.

Psychologically, however, they had been prepared for the American invasion. The fighting elements of the PDF were tough, disciplined and well trained. A high proportion had in fact been trained at the U.S. Army School of the Americas which located in Panama from 1946 to 1984 when it was transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia. The PDF did a good job on brainwashing its soldiers, as do all armies, in the matter of discipline, loyalty to the flag and laying down of life for country and cause. The cause, apart from occasionally subduing un-armed civilian protesters, was to defend Panama from the Yankee aggressor, according to Noriega and his group.

The Panamanian soldiers who refused to surrender at the urging of the U.S. troops bellowing through their bellhorns, were doing their duty. The ones who shed their uniforms and melted into sidestreets and mountainsides can hardly be blamed for their pragmatism.

The Panama Defense Forces had grown into a powerful institution within the Republic especially in recent years as Panama anticipated taking over the defense of the Panama Canal.

For her first 50 years as a republic, Panama had a civil police force known as the National Police Corps. The U.S. armed forces were always on hand if need arose. President José Antonio Remón Cantera began to institutionalize the force in the early 1950s, re-naming it the National Guard. Much of the systematic training he introduced was acquired at the U.S. Army School of the Americas in Panama, of which the National Guard was the third largest user. It became a combined force, having both police and military functions.

The Torrijos-Carter Treaty, implemented in 1979, changed the concept of the U.S. providing defense for both the Canal and Panama itself. Under the treaty, Panama was to share the defense role for 20 years and assume the mantle completely in the year 2000 when the Canal becomes Panama’s property.

To grow, the National Guard needed money and of course much of it came from the United States. From 1982, until aid was suspended in July 1987, the Panama military machine received over $105 million in direct aid and credits, a tiny proportion of the U.S. worldwide assistance to armed forces, but enough for little Panama’s army to develop a good deal of muscle.

cont’d below

Jones, Kenneth J., The Enemy Within: Casting Out Panama’s Demon

Copyright © 1990 Focus Publications, (Int.), S.A.

Showing posts with label FOF. Show all posts

Showing posts with label FOF. Show all posts

Tuesday, March 6, 2007

FEMALE ON THE FLOOR! The storming of Panama *6

cont’d from post above

In his element at this expansion, Noriega, when he took over as Commander in 1983, put his personal stamp on the old National Guard by re-naming in the Panama Defense Forces. This was formalized by Law 20 of September 29, 1983. At the time of the U.S. invasion, the total strength of the PDF was about 15,000, but it counted only about 3,500 fighting men in two combat battalions and eight light infantry companies. This was supplemented by a navy with 400 personnel, two patrol craft, two coast guard cutters and 13 launches; and an airforce with 500 personnel, four armed military reconnaissance planes, eight transport planes and eight other light planes.

What Law 20 did not promulgate was the formation of Noriega’s infamous “Dignity Battalions”’ a civilian para-military force intended as a “Home Guard”. It was supposed to consist of a broad cross-section of the society and at one time in 1988, Government workers of all categories from heads of department down were served “conscription” notices requiring them to report for Dignity Battalion duty—or else. The hardcore of its membership, however, comprised criminal and questionable elements of the professional unemployed for whom the incentive of free meals and the status of a gun was irresistible.

Nevertheless, the Dignity Battalions caused the problems for the U.S. army long after the infantry battalions of the regular PDF had been killed, surrendered or fled.

About seven hours after “H hour”, most of the organized resistance was crushed and the war was over. The fighting, however, was not. As the tropical sun of Day 1 rose in the blue sky to beat down upon American patrols newly arrived from icy regions, sniping groups from Dignity Battalions and possibly PDF soldiers in civilian clothes added considerably to their discomfort.

One serious blunder committed by the U.S. invasion strategists was allowing the Government radio station, Radio Nacional to broadcast all that morning. While the U.S. Forces Channel 8 and one other commercial TV channel urged citizens to stay inside, announcers of Radio Nacional screamed a constant message: “ Go out and face the aggressors … be prepared to die for your country”. Noriega’s principal bodyguard Lt. Asuncion Gaitan went on the air to announce that Noriega was “well and in a safe place”. He also gave a series of specific messages, using code names and instructions.

A typical message was this one to the Dignity Battalions: “Operate in small groups during the day or look for positions and mix with the people who support you and at night move and act against the enemy position in the periphery of the city”. Noriega’s voice was also heard on a private FM station exhorting the people to resist. In the afternoon, the U.S. shelled the Radio Nacional studio which was in a high-rise government building overlooking the bay on Avenida Balboa.

By Day 3, with U.S. troops still meeting resistance in Panama City, Gen. Maxwell Thurman, commander-in-chief- of U.S. Southern Command admitted that the mission was much tougher than expected. He declared that his soldiers were fighting “a real war” as they struggled to suppress an estimated 2,000 well-armed Noriega loyalists.

General Thurman’s own headquarters even came under attack by mortar and machine gun fire in the fourth day of the conflict, causing officers and journalists at a briefing to dive for the floor. At the same time, the nearby headquarters of the PDF traffic police, at Ancon, which was in American hands, was fiercely attacked. At the time it was full of former PDF members who had surrendered and volunteered to form a new police force. The attack was obviously aimed as much against the Panamanians as the Americans. Eye witness accounts from other areas of conflict tell of PDF soldiers being gunned down by members of the Dignity Battalions as they surrendered.

to be continued in future posts

Jones, Kenneth J., The Enemy Within: Casting Out Panama’s Demon

Copyright © 1990 Focus Publications, (Int.), S.A.

In his element at this expansion, Noriega, when he took over as Commander in 1983, put his personal stamp on the old National Guard by re-naming in the Panama Defense Forces. This was formalized by Law 20 of September 29, 1983. At the time of the U.S. invasion, the total strength of the PDF was about 15,000, but it counted only about 3,500 fighting men in two combat battalions and eight light infantry companies. This was supplemented by a navy with 400 personnel, two patrol craft, two coast guard cutters and 13 launches; and an airforce with 500 personnel, four armed military reconnaissance planes, eight transport planes and eight other light planes.

What Law 20 did not promulgate was the formation of Noriega’s infamous “Dignity Battalions”’ a civilian para-military force intended as a “Home Guard”. It was supposed to consist of a broad cross-section of the society and at one time in 1988, Government workers of all categories from heads of department down were served “conscription” notices requiring them to report for Dignity Battalion duty—or else. The hardcore of its membership, however, comprised criminal and questionable elements of the professional unemployed for whom the incentive of free meals and the status of a gun was irresistible.

Nevertheless, the Dignity Battalions caused the problems for the U.S. army long after the infantry battalions of the regular PDF had been killed, surrendered or fled.

About seven hours after “H hour”, most of the organized resistance was crushed and the war was over. The fighting, however, was not. As the tropical sun of Day 1 rose in the blue sky to beat down upon American patrols newly arrived from icy regions, sniping groups from Dignity Battalions and possibly PDF soldiers in civilian clothes added considerably to their discomfort.

One serious blunder committed by the U.S. invasion strategists was allowing the Government radio station, Radio Nacional to broadcast all that morning. While the U.S. Forces Channel 8 and one other commercial TV channel urged citizens to stay inside, announcers of Radio Nacional screamed a constant message: “ Go out and face the aggressors … be prepared to die for your country”. Noriega’s principal bodyguard Lt. Asuncion Gaitan went on the air to announce that Noriega was “well and in a safe place”. He also gave a series of specific messages, using code names and instructions.

A typical message was this one to the Dignity Battalions: “Operate in small groups during the day or look for positions and mix with the people who support you and at night move and act against the enemy position in the periphery of the city”. Noriega’s voice was also heard on a private FM station exhorting the people to resist. In the afternoon, the U.S. shelled the Radio Nacional studio which was in a high-rise government building overlooking the bay on Avenida Balboa.

By Day 3, with U.S. troops still meeting resistance in Panama City, Gen. Maxwell Thurman, commander-in-chief- of U.S. Southern Command admitted that the mission was much tougher than expected. He declared that his soldiers were fighting “a real war” as they struggled to suppress an estimated 2,000 well-armed Noriega loyalists.

General Thurman’s own headquarters even came under attack by mortar and machine gun fire in the fourth day of the conflict, causing officers and journalists at a briefing to dive for the floor. At the same time, the nearby headquarters of the PDF traffic police, at Ancon, which was in American hands, was fiercely attacked. At the time it was full of former PDF members who had surrendered and volunteered to form a new police force. The attack was obviously aimed as much against the Panamanians as the Americans. Eye witness accounts from other areas of conflict tell of PDF soldiers being gunned down by members of the Dignity Battalions as they surrendered.

to be continued in future posts

Jones, Kenneth J., The Enemy Within: Casting Out Panama’s Demon

Copyright © 1990 Focus Publications, (Int.), S.A.

FEMALE ON THE FLOOR! Forks in the Road

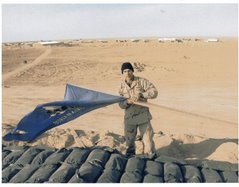

A few days ago, Mom chided me on referring to the troops I was surrounded by as “even less promising than me.” I really meant that statement, but I’ll explain a little better.

Though I can’t say how it is for all wars, I can only relay how it was for mine. I was locked down in my section except for those blessed times I had to ride across the bridge with SFC Grover (or whatever we named him) who totally creeped me out. Most of the people in my section at that time were on their way out. In fact, some were still there because of the invasion, so since their mission was different than mine plus the fact that they were entirely, well, unhappy, I was rarely around them. They went out on missions I know not of. After our day missions were complete, we spent the night in the section building. We never went back to the barracks except for a shower. No one was in the barracks except whoever was on duty there. We slept where we worked.

Did anyone miss that my mission was coffee? Now I ask you, what’s to be happy about?

I have been “non-traditional” my entire life. Either too young or too old. At least as far as military and education are concerned, so X out young on the prior sentence. But in the military, everyone my age and even those much younger, far outranked me. According to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, I was allowed to fraternize with E-4’s and below. I was E-4; SFC Grover was E-7. He knew better and I let him get by with it. Just wisecracks, nothing more. Anyone in the military knows that there are jerks within its ranks, just as there are within the general population. It happens.

I did get transferred out of the section for nine months until he retired. This was at my request shortly after the war. Yet still, throughout the nine months, he just seemed to become more enraged with my request for a transfer. It wasn’t about a desire for me; it was about getting even. He finally went too far when he shook his finger at me from across the table, his face turned as red as his hair. His head seemed to swell up, threatening the elastic that held his rape-proof glasses square across his beet nose, then he growled, “You’re mine and I’m getting you back! We’re getting a forklift this week and I hold the slot for you!” He did this in front of a bunch at the chow hall one day, including a couple that outranked him. Everyone got very quiet, and after that, he never bothered me. He avoided me. The hateful man retired from the military and is most likely impressing someone in the civilian sector today.

The part that may truly surprise you on this is that I transferred to DSU or Direct Support Unit as a forklift driver and as the Materiel and Storage Handling Specialist I had been trained to be. My new job would be to receive Class IX repair parts for the Heavy Equipment the 536th used. Some of the tires were as big as my den!

In S-4, ‘S’ meaning Staff, I would have worked in a cozy air conditioned office in Battalion Headquarters, supplying only that level with office supplies, etc., whereas in DSU, I worked in a hot warehouse and my only air came from those huge fans the DOD possesses. You know the ones I’m talking about. They too, are the size of my den. Do they still have those black pens that say U.S. Government on them?

We were locked down in our sections until sometime after January 3, 1990. That was the day Noriega was captured, and it was also my sister’s birthday.

Life in the barracks wasn’t too bad and Ft. Kobbe and Howard Air Force Base were a nice little place, though to really accomplish anything, we did have to go across the bridge.

Panama was beautiful so long as you looked at eye-level or up. It was a developing country whose people threw their trash around a lot on the beaches close to us. We had Ft. Kobbe Beach, and then there was also Vera Cruz Beach, which I always referred to as Very Crude Beach, because of the aluminum cans tossed about and the occasional diaper or two. But the bases were clean.

And over the years, I’ve come to appreciate their culture. But back then, I was fifteen minutes early, ASAP and Priority, and the Panamanians, who I had to deal with a great deal before it was over, they were always “mañana o lunes.”

I was Type A.

Is there a Type D?

Though I can’t say how it is for all wars, I can only relay how it was for mine. I was locked down in my section except for those blessed times I had to ride across the bridge with SFC Grover (or whatever we named him) who totally creeped me out. Most of the people in my section at that time were on their way out. In fact, some were still there because of the invasion, so since their mission was different than mine plus the fact that they were entirely, well, unhappy, I was rarely around them. They went out on missions I know not of. After our day missions were complete, we spent the night in the section building. We never went back to the barracks except for a shower. No one was in the barracks except whoever was on duty there. We slept where we worked.

Did anyone miss that my mission was coffee? Now I ask you, what’s to be happy about?

I have been “non-traditional” my entire life. Either too young or too old. At least as far as military and education are concerned, so X out young on the prior sentence. But in the military, everyone my age and even those much younger, far outranked me. According to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, I was allowed to fraternize with E-4’s and below. I was E-4; SFC Grover was E-7. He knew better and I let him get by with it. Just wisecracks, nothing more. Anyone in the military knows that there are jerks within its ranks, just as there are within the general population. It happens.

I did get transferred out of the section for nine months until he retired. This was at my request shortly after the war. Yet still, throughout the nine months, he just seemed to become more enraged with my request for a transfer. It wasn’t about a desire for me; it was about getting even. He finally went too far when he shook his finger at me from across the table, his face turned as red as his hair. His head seemed to swell up, threatening the elastic that held his rape-proof glasses square across his beet nose, then he growled, “You’re mine and I’m getting you back! We’re getting a forklift this week and I hold the slot for you!” He did this in front of a bunch at the chow hall one day, including a couple that outranked him. Everyone got very quiet, and after that, he never bothered me. He avoided me. The hateful man retired from the military and is most likely impressing someone in the civilian sector today.

The part that may truly surprise you on this is that I transferred to DSU or Direct Support Unit as a forklift driver and as the Materiel and Storage Handling Specialist I had been trained to be. My new job would be to receive Class IX repair parts for the Heavy Equipment the 536th used. Some of the tires were as big as my den!

In S-4, ‘S’ meaning Staff, I would have worked in a cozy air conditioned office in Battalion Headquarters, supplying only that level with office supplies, etc., whereas in DSU, I worked in a hot warehouse and my only air came from those huge fans the DOD possesses. You know the ones I’m talking about. They too, are the size of my den. Do they still have those black pens that say U.S. Government on them?

We were locked down in our sections until sometime after January 3, 1990. That was the day Noriega was captured, and it was also my sister’s birthday.

Life in the barracks wasn’t too bad and Ft. Kobbe and Howard Air Force Base were a nice little place, though to really accomplish anything, we did have to go across the bridge.

Panama was beautiful so long as you looked at eye-level or up. It was a developing country whose people threw their trash around a lot on the beaches close to us. We had Ft. Kobbe Beach, and then there was also Vera Cruz Beach, which I always referred to as Very Crude Beach, because of the aluminum cans tossed about and the occasional diaper or two. But the bases were clean.

And over the years, I’ve come to appreciate their culture. But back then, I was fifteen minutes early, ASAP and Priority, and the Panamanians, who I had to deal with a great deal before it was over, they were always “mañana o lunes.”

I was Type A.

Is there a Type D?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)