Matt Freed, Post-Gazette

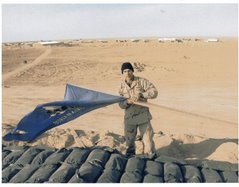

Chief Warrant Officer Paul S. Dziegielewski and Sgt. 1st Class Don Hammons are Army officers who notify families of a soldier's death and work with the family to make funeral, financial and other arrangements.

Chief Warrant Officer Paul S. Dziegielewski and Sgt. 1st Class Don Hammons are Army officers who notify families of a soldier's death and work with the family to make funeral, financial and other arrangements.

Beyond words

Sunday, February 20, 2005

By Lillian Thomas, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Matt Freed, Post-Gazette

Chief Warrant Officer Paul S. Dziegielewski and Sgt. 1st Class Don Hammons are Army officers who notify families of a soldier's death and work with the family to make funeral, financial and other arrangements.

The casualty officer who must notify a family that a soldier has died can never predict what will happen after he knocks on the door.

A parent might fall down on the floor in front of him; a wife might scream at him and push him out of the house; a sister might hug him so hard it hurts.

What Chief Warrant Officer Paul Dziegielewski remembers is "the eyes piercing through your body -- they see you but they don't see you."

Dziegielewski, the casualty officer for the Army Reserve 99th Regional Readiness Command in Moon, is in charge of preparing soldiers to do notification visits and to become casualty assistance officers who will work with families from the day of notification until all funeral, financial and other arrangements are settled, and often well beyond.

The 99th encompasses five states and handles deaths of both reserve and active duty soldiers, as well as civilians employed by the Army and retirees. It's one of the busiest reserve commands in the nation, and the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have meant many more deaths to report.

"We haven't had war like this since Vietnam," said Dziegielewski, who said the 99th has handled 263 notifications since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 -- seven from the Pentagon, three from Afghanistan, 101 from Iraq and the remaining 152 involving soldiers who died throughout the United States.

Both the casualty notification and casualty assistance jobs are on the duty roster and are assigned on the basis of what officer is at the top of the list. It's not a job you can refuse, said Dziegielewski.

"It's a duty you inherit by virtue of being a soldier," said Sgt. 1st Class Jeff Murphy of the 99th, who did his first notification during the Gulf War.

The Army makes sure the officers who do the notifications do not do the later funeral arrangement work for relatives. "Most families never want to see you again -- you're that grim reaper," said Dziegielewski.

The notification team tries to inform the primary next of kin, who is listed on a form every soldier fills out, within four hours of confirming the death. The notification officers work from a casualty report that sometimes includes time, date, location and circumstances of death (though in some cases those are not yet known).

Their instructions are to make sure they are talking to the right person, tell that person that the soldier has died and answer questions. If the family member is alone, the notification officer will get another relative, a neighbor or friend to stay with him or her before leaving.

There is a canned speech, one that begins "The Secretary of the Army has asked me to express his deep regret ... " but usually the appearance of a pair of soldiers in dress uniform, sometimes accompanied by a chaplain, is more than enough to let the family know what has happened.

Dziegielewski, the casualty officer for the 99th, has been on a half dozen notifications. He's never made it through the entire formal address, he said, because the families know why he's there.

Sometimes it doesn't work that way, though.

A pause, then a breakdown

Sgt. 1st Class Donald Hammons went on his first casualty notification visit in May.

"I had always heard and assumed that when you appear at the door, they know why you are there," he said. But the mother of Spc. Mark Kasecky, 20, of McKees Rocks, greeted them and invited them in graciously, making polite conversation.

"When you think about giving the speech, you don't think you'll give the whole speech," he said. "After I finished, then there was that dramatic pause, then she broke down."

More important than the words is "being a human being," said Dziegielewski.

He tries to make sure the family members are sitting down (he once had a mother-in-law keel over backward and her daughter -- the soldier's wife -- fly at him in fury). He tells them the soldier has died, not "passed on" or some other euphemism. He listens to whatever they have to say. He stays if he's wanted, gets out if he's not.

cont'd below

No comments:

Post a Comment