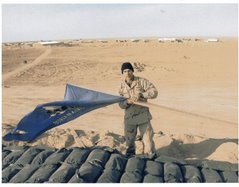

ON THE MORNING OF JUNE 17, Coons didn’t show up at the camp’s communications center. It was the first time since arriving in Kuwait that he hadn’t made it to work. Later that morning, he called his company commander. His voice was slurred. “Please come get me,” he said.

He was found on the floor in his trailer, a bottle of Neurontin beside him. He was semiconscious, mumbling half sentences about “seeing this guy.” At the base hospital, it was determined that he had swallowed six or seven pills. “Were you trying to commit suicide?” asked an Army doctor who had been brought in to talk to him.

Finally, Coons decided to talk to someone outside his family about the face of the young soldier. But according to the doctor’s report, Coons denied trying to commit suicide. “I never intended to kill myself,” he told the doctor. “That was never, ever a thought. I just wanted to go to sleep and get the visions of that kid out of my mind.”

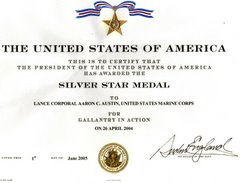

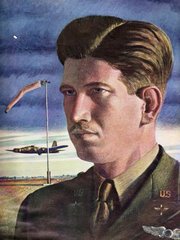

When Singleton and the camp’s sergeant major came to visit Coons, he told them that he had overdosed on Neurontin only because he was desperately trying to fall asleep. He said he felt that he had let down his fellow soldiers and that he had ruined his career. Singleton said that the incident would probably not have any impact on his enrollment at the Sergeants Major Academy, which Singleton later admitted he said only to comfort Coons. There was no question in Coons’s mind that his career had been seriously damaged. Regardless of how nobly he had served in the past—his Bronze Star had been approved by the Pentagon less than a month earlier—his fear was that he would forever be known as just one more soldier who had “gone mental.”

In fact, his commanding officers had already decided that the time had come to move on without him. They did not let him return to his post, not even to say good-bye to his friends. Coons spent a few more days at the base hospital, where he paced the floors and read the Bible. He called Robin and his parents to tell them that he had had “a breakdown.” He then said, strangely, that he didn’t want to go into detail about what had happened because people were watching him.

It was obvious that his mind was continuing to misfire. He admitted to the hospital’s staff that he was still seeing the young soldier’s face. He also admitted that on those occasions when he was able to see his own face in the mirror, he would find himself studying it, focusing on what he said were blemishes on his skin.

On June 21, he was shipped to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, in Germany, the Army hospital where all wounded soldiers from Iraq are sent. A soldier there who met Coons said that he was acting “very strange . . . [He] would begin a conversation [and] then would jump to another subject and then back again to the original. He also would keep conversations going once you ended it and walked away.” According to the soldier, Coons did not mention his mental breakdown. Instead, he’d made up a story that he was being sent home because he had used too much force while interrogating a suspected insurgent.

But a Landstuhl psychiatrist who evaluated Coons noted in his report that the master sergeant maintained a “professional demeanor.” He added that Coons’s “risk for suicide is assessed as low”—a startling conclusion considering the Neurontin overdose just four days earlier.

Perhaps the doctor believed that Coons would find some semblance of normality once he returned home to his family. Perhaps he believed that all soldiers suffer some sort of emotional trauma during wartime and that little could be done about it. Or perhaps the doctor, overwhelmed by the number of soldiers coming in each day to Landstuhl, simply had little time to evaluate Coons.

By then, about three months after the invasion of Baghdad, it was becoming clear to military experts that this war—with its close-up urban warfare, the elusiveness of the insurgents, the constant threat of roadside bombs, the mutilated bodies, and the high number of civilian killings—had become the perfect breeding ground for mental health problems in soldiers. Surveys taken of the first wave of troops leaving Iraq were already indicating that a fifth of the soldiers qualified as having “moderate or severe” mental health problems—a totally unexpected number.

It is quite possible that for all the questions surrounding Coons’s condition, the psychiatrist felt obligated to focus his attention on his most severe cases. So he arranged for Coons to receive outpatient care upon his return to the United States, and papers were signed for Coons to be put on a military airplane and flown with other wounded soldiers to the 260-bed Walter Reed hospital. Before leaving Germany, Coons called Robin and told her he would be at Walter Reed for only a few days of “follow-up” counseling and that he would be back in Texas by early July. There was no need for her to come see him, he said.

Wearing his uniform, he arrived at Walter Reed in the early morning hours of June 29 and met with a third-year resident in one of the hospital’s locked psychiatric wards. In his report, the resident made note of Coons’s excellent grooming and “appropriate military bearing.” He noted that Coons acted “surprised” to be in a psych ward and that he adamantly insisted that he had had no suicidal thoughts. But the resident may have been overwhelmed by the influx of patients. Press accounts from 2003 reported that the members of Walter Reed’s medical staff were working seventy- to eighty-hour weeks. The resident quickly released Coons to a room at the Mologne House, a hotel on the Walter Reed campus for visiting families and soldiers undergoing outpatient treatment, and told him to report the next morning to the outpatient mental health clinic.

A CLERK AT THE MOLOGNE HOUSE gave him a key to room 179, and for the first time since his overdose on June 17, Coons found himself alone. He put a Do Not Disturb sign on the door and locked it. He only partially unpacked his belongings. He made no telephone calls. Apparently, he picked up a Bible and turned to the Book of Psalms, placing a bookmark at a psalm in which the writer asked God to release the demons inside him.

He did not appear the next morning for his appointment at the mental health clinic. No one from the clinic or the Mologne House came by to check on him. Seeing the Do Not Disturb sign, the hotel’s maids moved on to the next room.

Later that day, Robin called the hospital, but when she was connected to his room, he did not answer. Both Robin and Carol called the next day. Again, no answer. And again, no one went looking for him.

One can only guess what was happening to him. Maybe Coons was feeling good about himself after convincing the young resident that he did not belong in the psych ward. Maybe he was still telling himself that all great soldiers should be able to overcome any adversity. Maybe he still believed that he could get through his suffering alone, soothed only by a passage or two from the Bible.

Or maybe he walked into the hotel room, looked into the bathroom mirror, and again saw the soldier’s face, the skin blistered with burns. Maybe he stood there for a few moments, realizing that the face would never leave him. Maybe, after another sleepless night, he decided that it would be unfair to bring the face back to Texas, back to his beautiful wife and children.

Tuesday, June 12, 2007

Casualty of War 4

Labels:

Casualty Officers,

Coons,

Gold Star Families,

OIF history,

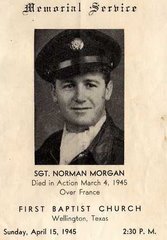

sacrifice,

Shared Works

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment