ON JULY 2, ROBIN CALLED THE MOLOGNE HOUSE several times, leaving messages on the voice mail for room 179. She spoke to a clerk at the front desk, asking if anyone had seen her husband. She called the chaplain’s office and asked a chaplain to check on Coons. Robin said to the woman, “I just want you to knock on his door and say, ‘Master Sergeant Coons, are you okay?’” But, according to Robin, the chaplain replied that because of Coons’s rank, she didn’t have the authority to, as she put it, “get into his business.”

“You mean you’d go check on a young soldier, but you won’t check on an older soldier who’s given seventeen years of his life to his country?” Robin asked.

“I’ll see what I can do,” the chaplain said. But Robin says she never heard from her again.

On July 3, Carol called the hospital’s security desk and asked one of the police officers to look for her son. He too said he would be in touch.

But more hours passed. On July 4, at two-fifteen in the morning, a tearful Robin called the desk clerk at the Mologne House. “All I want to know is if anyone has seen him,” she said. “Maybe he’s left the hospital and is headed home. Can’t you just open the door to his room and see if his suitcase is still there?”

According to his original orders, Coons was supposed to be home by July 4, Independence Day. Robin, Carol, and Richard had planned a welcome-home party, and although they had not heard from him, they decided to go ahead and decorate the house, hoping he might suddenly appear. They planted American flags in the front yard. They spent a couple hundred dollars on beer and barbecue. Robin put together red-white-and-blue outfits for her and the girls to wear.

But he did not arrive, and he did not call.

“My God, he’s been missing for four days,” Robin said to another clerk at the Mologne House. “Please look for him! Please!”

At 5:59 on the morning of July 5, she heard her doorbell ring. She slipped out of bed—her two girls were still asleep beside her—walked to the front door, and looked through the peephole. She saw a red U.S. Army beret. Her heart began pounding. “He’s home!” she screamed and opened the door. “It’s James!”

But it wasn’t her husband. Wearing the beret was an officer from Fort Hood. Beside him was an Army chaplain. “Mrs. Coons, may we come in?” the officer said.

She sagged against the door.

“Mrs. Coons, may we come in?” the officer said again.

“No, not until you tell me everything is okay with my husband.”

There was silence. “We can’t tell you that, Mrs. Coons. I’m sorry. We can’t tell you that.”

THEY DID NOT TELL HER HOW HE HAD DIED. They did not tell her that an employee on the night shift had finally gotten a key, opened the door to her husband’s room at four o’clock in the morning on July 4, and found the master sergeant hanging from a white bedsheet that was wrapped around his neck and then tied to an exposed water pipe in the ceiling.

They simply told Robin that Coons had passed away at Walter Reed. When she asked if he had suffered a heart attack or a stroke, they said they did not know. A casualty officer later arrived from Fort Hood to help Robin plan the funeral, but she told him that Coons had already taken care of that. Friends were also stopping by. Many of them had not heard the news and were expecting to see Coons himself, thinking he was home.

His body arrived in Houston on July 11 and was taken to a funeral home in Conroe. Only then did the casualty officer take the family aside and provide details about the hanging. Robin became hysterical. “And no one once went to check on him!” she screamed, the sound of her voice echoing through the funeral home. “Not once!”

For the funeral, Coons was attired in his dress uniform, which he had requested in his note in the gray folder. A few soldiers who had known him for years offered short eulogies—Coons had said he wanted no long speeches—and then outside the funeral home, an honor guard from Fort Hood gave him a 21-gun salute. The Army allowed a couple of officers from his company in Kuwait to fly in for the funeral, and afterward, at the reception, they kept telling Robin that they’d had no idea that Coons was that sick.

“He overdosed on sleeping pills,” she said. “Didn’t anyone at the base realize what condition he was in?”

“We thought he would overcome it,” one of the officers said. “If anyone could overcome it, Coons could.”

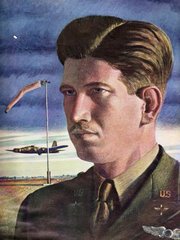

A few days later, Robin and Coons’s parents drove to Fort Hood to get Robin and her daughters signed up for military and Social Security benefits. While they were there, an officer from the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command unexpectedly showed up to ask them some questions about Coons. Was he troubled as a boy? Had he previously shown signs of mental illness? Furious, Carol told the officer to quit referring to her son as “he” and start referring to him as “Master Sergeant Coons.” “My son wasn’t crazy,” she said. “He wasn’t a coward. He was a soldier. You go look at his record. You can only hope you do in your career what he did in his.”

An officer involved in the investigation into Coons’s death concluded that no one at Walter Reed, from the third-year psychiatry resident to the staff members of the Mologne House, had been negligent in his responsibilities. But Robin called the officer and said, “Oh, no. We need more answers.” In August, she, Richard, and Carol flew to meet with officials at Walter Reed.

Tuesday, June 12, 2007

Casualty of War 5

Labels:

Casualty Officers,

Coons,

Gold Star Families,

OIF history,

sacrifice,

Shared Works

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment